I point my flashlight through the night air at a white-coloured object on the road, thinking I have found a baby puffin. My excitement turns to disappointment when I realize it is nothing more than a discarded Tim Horton’s coffee cup lid.

A light rain falls as I wander the streets of the tiny coastal town of Witless Bay, a short drive south of St. John’s, the capital of Newfoundland and Labrador. I am searching for baby birds because I have joined the Puffin and Petrel Patrol. It is a dedicated band of volunteers who comb the streets of communities near the Witless Bay Ecological Reserve every late summer, looking for fledgling birds that are drawn to the towns’ artificial lights, confusing them for the moon and the stars by which they navigate to sea.

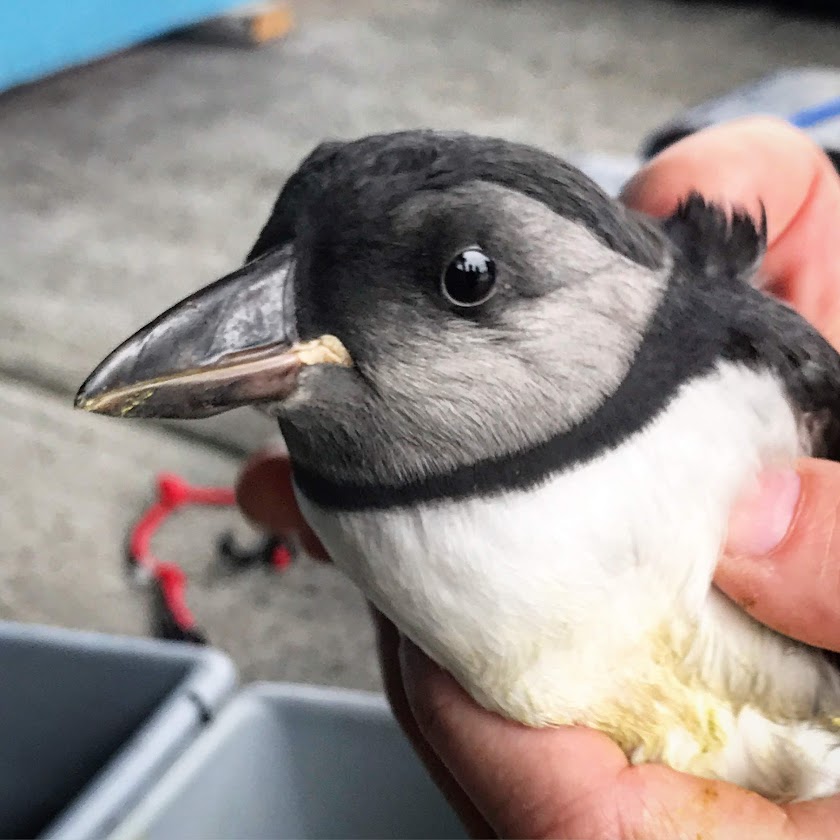

The thing about puffins and baby puffins—more properly known by the all-too-cute name of pufflings— is that they are much better swimmers than fliers. If these six-week-old baby birds become stranded on land, they aren’t always able to get back to sea without human help. The patrol spends hours every night during the fledgling season in August and September rescuing hundreds of these birds before they become injured or killed by cars or predators.

Each morning after a patrol, the birds are measured and released, either from local tour boats or from the beach, so they can fly out to sea where they will spend the next four or five years maturing on the open ocean before returning to reproduce on the rocky islands of Witless Bay Ecological Reserve. At 260,000 pairs of birds, this is North America’s largest Atlantic puffin colony.

Before I head out to search for pufflings, I meet Juergen Schau who, along with his wife, Elsie, are the founders of the Puffin and Petrel Patrol. Schau, a former executive for Sony Pictures Entertainment in Germany and Austria, bought a summer home in Witless Bay. In 2004, the couple found themselves rescuing pufflings and housing them in their garage. It wasn’t long before locals started helping out and the patrol was born.

“I think that this little bird touches people’s hearts,” says Schau. “Over the years, we have saved maybe 10,000 birds. It’s not a big number, but we are helping change people’s behaviour and educating them, which is enormous.”

With some wearing orange safety vests and carrying nets, patrollers are easy to spot. There’s an excitement in the air as we wander the dark streets. It reminds me of trick-or-treating on Halloween as a child, but, instead of candies, we are gathering pufflings. I have no luck finding any on my first night, but vow to do better the next.

Since founding the patrol, Schau has partnered with the Newfoundland and Labrador chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS). While CPAWS boasts several hardcore supporters in the local community to help with this conservation movement, volunteers—it limits the number each year to avoid stress on the birds—come here from far and wide to help. People like Kathy Williams and her 16-year-old daughter, Alexa, who have been journeying from Philadelphia every summer for the past seven years. This August will mark their eighth season. “Some people go every year to Disney; we come here to save puffins,” says Kathy.

I am out again the next night. The moon is half-full, which is a good thing for the puffins because they are more likely to navigate safely to sea. After hours of fruitless searching, I find nothing. I was warned there’ no guarantee you will find a bird, and I’m starting to doubt I ever will.

Night three and I’m out again. Third time’s the charm, they say, but I also find I am starting to think like a puffin. I head to one of the patrol’s historic hotspots, a warehouse with bright spotlights, and, within minutes, I spot my first puffling. I don’t know who is more surprised, the bird or me. My heart pounds as I catch him (her?) with my net and place the bird into a plastic crate. He does not appreciate my efforts and nips at one of my fingers with his beak. Safely in the crate, I carry the puffling back to the car. Returning to the street, I find a second bird. He’s a bit harder to catch, but I soon gather him up.

The birds are agitated as I drive them over to patrol headquarters, so I sing nursery rhymes to calm them down. “Rock-a-bye baby puffings, in their little box. When the wind blows, the puffings will rock.” For a brief moment, they’re quiet, but soon resume their racket.

The next morning, I venture down to the beach to watch the release of the pufflings. Normally, only local volunteers release the birds, but the crowd is thin on this misty morning so I am allowed to free one that I rescued—it is one of more than 600 that were recovered during the 2018 season.

“Go to the sea, little bird,” I shout as I toss him up into the sky. I watch as he flaps his wings and flies into the horizon. I make a wish that he stays safe and comes back to Witless Bay to help grow the next generation of puffins.

- This story was originally published in the August 2019 issue of Westjet Magazine.